Carbon Accounting: From Burden to Value

A plea for common sense to make carbon accounting a constructive tool rather than an expensive tax on sustainability

TL;DR “Carbon accounting” has become a bureaucratic nightmare. We have burdened the limited exercise of counting carbon across our economy with a complex taxonomy intended also to plan strategically, set goals, pressure key actors into action, etc. This has led to wasted resources, poor data quality, non-compliance, and an inability to aggregate information to allocate resources. We must fix it urgently given the scale of the problem and the advent of AI. New tools can unlock tremendous value but only if we build on top of good data and with functional frameworks. At Avila, we support a simplification of carbon accounting to encourage rather than hinder an energy transition. One superior approach is the e-liabilities method, which follows the well understood principles of financial accounting. When successfully implemented, this method provides reliable data covering nearly all value chain emissions, setting the stage for true carbon tracking and reduction incentives.

At Avila, we favor a pragmatic approach to sustainability. Climate advocates risk losing the support of the global majority if they ignore the economic, cultural, and geopolitical realities in which an energy transition must occur and impose irrational burdens to meet our goals.

One perfect example of excessive burden – luckily highly solvable – is carbon accounting. It has ballooned into a bureaucratic nightmare. Decades of layered solutions to achieve different goals have led us to lose sight of the core objective: measuring emissions to align investment with decarbonization.

Like any other bureaucracy, the ecosystem of NGOs, regulatory bodies, consultants and vendors has exploded as new standards, guidelines and rulings are developed in the name of standardization and better information, but which in practice increase complexity and non-compliance. The current approach consumes precious limited resources and requires assumptions that obfuscate the validity of the information and create ample room for errors and gamesmanship.

Companies are scaling back reporting commitments (see Morgan Stanley example below) given their inability to meet disclosure standards, though they remain committed to “Net Zero”, proving reporting has become a compliance exercise, not a driver of action.

For example - we recognize a child’s grades do not capture his or her work ethic, social skills, kindness, or other developmental goals, but we know a quantified dataset for this would be highly arbitrary. We solve for this with commentary and parent-teacher conferences. In business accounting, we recognize the numbers do not shed light on employee morale, product pipelines, customer satisfaction or other critical value drivers, but we do not mandate granular and regular reporting as we know the data would be rife with assumptions and unauditable. We fill this gap with management forecasts, strategic plans, etc.

Why should carbon be any different than the examples above? A desire to know a company’s full emissions impact and demand specific reductions cannot be solved with a gargantuan data-estimation undertaking without actual data. Furthermore, it fuels further criticism from those who do not prioritize climate today and argue resources are not destined to good use.

Our view is that the emissions-tracking-and-reduction industrial complex must clearly differentiate between (1) the high level frameworks that help understand emissions drivers and how best to reduce them, and (2) the rigorous carbon accounting that granularly tracks emissions throughout our system.

Despite this being a long-held belief at Avila, we are voicing our concerns more loudly now for two key reasons.

First, the scale of the problem has gotten out of hand. When we are spending more on reporting than innovation, we know we are not on the right path.

“Spending on sustainability reporting exceeds spending on sustainability innovation by 43%”

‘The Business Value of Sustainability’ IBM Institute for Business Value, February 2024

We cannot afford to waste resources essential to accelerate a transition. Imagine if half of all the resources devoted to AI development in recent years had been allocated to measuring its impact, how much slower would progress be?

Second, digital tools are rapidly coming to market to help companies track their data, as shown in the market map below. It would be a lost opportunity to start this off on the wrong frameworks and inputs.

With the rapid advance of machine learning and AI, we will soon be able to implement highly scalable systems that can penetrate every corner of our economy to track emissions accurately. The data we will feed these systems will power their evolution. We must ensure it is high-quality from the start. Given the black box nature of AI systems, beginning with low quality data could be difficult to fix later on.

SIDEBAR: A Short Primer

A Brief History

Emissions tracking can be traced back to the 1970s, with early scientific discussions on the environmental impact of industrialization. As multiple goals were pursued (not just counting carbon, but also pressuring major players to take maximum action across their entire sphere of influence), hundreds of global, regional, and country-specific sustainability reporting standards, initiatives, and frameworks were created by multiple organizations.

The timeline below highlights the key agreements and associated frameworks noting the various mandatory reporting obligations in place and upcoming across the US and EU.

Carbon Accounting Timeline - Key Events

More information on the various organizations and abbreviations in our Glossary.

The Current Dominant Frameworks: GHG Protocol & SBTi Targets

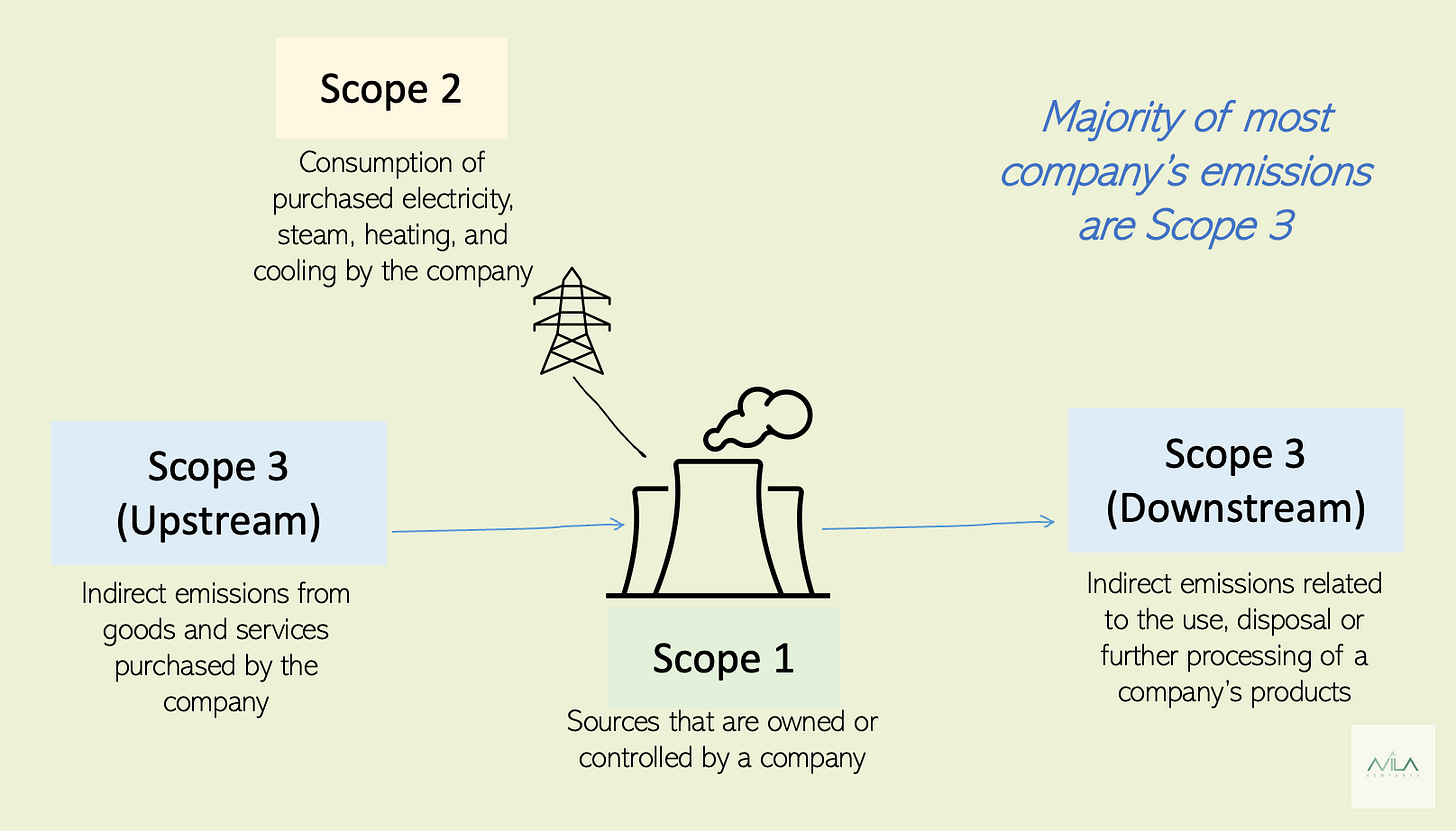

GHG Protocol sets accounting standards for greenhouse gases (“GHGs”, although inaccurately but commonly simplified to carbon). It rests on a classification into 3 Scopes. The original rationale was to create the right set of comprehensive incentives for major polluters to effect change. Scope 1 captured emissions within their direct control. Scope 2 carved out purchased electricity to encourage energy efficiency but without disincentivizing electrification, and putting the burden of greening electricity on the utilities. Scope 3 was left to capture everything else impacted by the company to encourage “systems thinking” and promote behavior that optimized for planet benefit vs. company benefit. Tautologically, the majority of impact of any single company on the entire ecosystem is outside their purview, thus Scope 3 emissions represent 90% of most companies’ reported information.

The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is a collaborative effort among CDP, the UN Global Compact, the World Resources Institute (WRI), and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). It serves as a target-setting mechanism that uses top-down global goals (i.e. to keep warming below 1.5°C, or reach net-zero by 2050), allocated by industry and activity. As one might imagine, this top down and centralized approach based on evolving targets can create its own set of complexities akin to a centrally planned economy.

Current State of Play

Despite the challenges, global mandates and/or a desire to support environmental initiatives have led to increasing adoption in recent years.

- GHG: In 2023, 23,000 companies representing two-thirds of global market capitalization engaged with the CDP to share at least some environmental data (a third of them for the first time). However, only a third of the companies managed to disclose Scope 3 emissions

- SBTi: Several thousands of companies have set commitments, but in 2024 over 200 companies, including Microsoft, P&G, Unilever and Walmart had “net-zero commitments removed”. About half of the total companies cited Scope 3 as too much of a challenge to setting net-zero targets.

The Challenges with the GHG Protocol (Scopes 1,2 and 3)

The logic underlying the emissions-tracking efforts over the past decades was to enable major emitters to understand where they were generating emissions and push for reductions across their entire sphere of influence. To do so, looking as far and wide as possible made sense. The first and obvious grouping was the emissions generated directly (labeled Scope 1). The purchased electricity was purposefully separated out (Scope 2) so companies would still be encouraged to electrify while utilities were tasked with migrating towards cleaner production methods. Finally, to encourage a holistic view and pressure companies to use their influence maximally on both suppliers (upstream emissions) and customers (downstream emissions), Scope 3 emissions were devised.

With such an expansive definition of Scope 3, it is tautological that they represent the vast majority of most companies’ emissions. Thus, practitioners concluded ignoring Scope 3 was tantamount to doing nothing. This was an understandable (albeit circular) concern. And yet - we disagree as it relates to granular reporting. Here’s why:

How Can We Fix the Current System?

We must clearly distinguish between (prospective, estimated) disclosures and carbon accounting. The latter can only cover actual data, preferably under the purview of the emitter. While the emissions-tracking industrial complex might disagree, we believe that absent better alternatives, simply limiting the granular carbon accounting to what we refer to today as Scopes 1 and 2 would be a step in the right direction. The smaller pool of data would be more accurate and actionable, more companies would report, and we would rely (as occurs today in practice) on sporadic consultative reports to assess full lifecycle impact and define strategic roadmaps for broader decarbonization.

However, we do not have to settle for that. A better solution exists in the form of e-liabilities. First proposed by Kaplan and Ramanna in 2021, and further developed at the E-Liability Institute (which just released its latest proto-standard), this approach tracks emissions in a manner similar to financial accounting. Just as the cost of a product is known from the supplier when it is purchased by a company, so would its embedded carbon be tracked. And just as the company would sell the product to its customer and record a sale price, it would transfer and record its embodied carbon at exit. This system allows emissions to be tracked as they move through the value chain, simplifying the accounting process and providing more reliable data.

In the world of e-liabilities, upstream Scope 3 calculations are unnecessary as the supplier provides the data. (We recognize in a transition period while suppliers adopt this system, emitters might need to continue using estimation methodologies but report them as an e-liability). As emissions get tracked throughout the product lifecycle, all “scopes” are accumulated until the final sale. Thus, in aggregate, the e-liabilities method captures all emissions except the final user’s.

In aggregate, the e-liabilities method captures all emissions (Scopes 1, 2 and 3) except the final user’s

End user emissions can be easily estimated in other ways in the future, and market/regulatory incentives/taxes imposed atop broadly adopted, generally accepted, verifiable data.

What arguments could be made against e-liabilities, and how do we see them?

While the e-liabilities approach has its limitations, its strength lies in providing reliable, auditable, common data as a foundation. A potential addition to this framework is the Emissions Liability Management (ELM) system, proposed by Roston, Seiger, and Heller, which matches carbon liabilities to carbon removal assets thus creating direct incentives for reduction. By starting with clear, manageable data and then adding accountability mechanisms like ELM, this approach offers a more practical way to drive meaningful change.

So What’s Next?

We recognize no system is perfect. However, current reporting has become an expensive compliance task rather than a tool for impact, diverting resources from true sustainability efforts and alienating potential market participants. We must do better.

Shifting gears is not easy, especially after so much hard work put in by smart and devoted experts. But we also see the massive opportunity to course correct. If we want sustainability to become or remain a priority in a complex world, we must consider better alternatives. We hope leading organizations such as E3G, PRI Association, and the SBTi partners consider improvements to drive climate action.

With the explosion of AI tools that could underpin new solutions, there is no time to waste in upgrading the backbone of emissions data gathering and reporting for minimum burden and maximum impact.

It is not too late. Now is the time to embrace simplicity and pragmatism.

At Avila, we look forward to collaborating with emitters, practitioners, and founders looking to advance this common-sense approach. If you are building in the carbon accounting and climate risk space and have ideas around these notions, please get in touch.

Huge thank you to advisor for her feedback on this post, and her hard work to push forward climate action

To discuss or learn more about Avila VC please reach out to us.

Follow us for sporadic postings on LinkedIn and X, and Patty Wexler on Medium